Editors Note

This edition does not have much in terms of recent caving adventures; however, I received a surprising amount of content despite the winter we have had to endure. A real highlight of this edition is Brendan Hall’s attempt to provide an answer the age-old mystery: ‘does weather at the surface really affect conditions underground?’ It turns out that, although we don’t actually know the answer yet, he’s already managed to procrastinate away most of the final year of his PhD so well done Brendan! There is also a semi-revealing photo of Nat Dalton he insisted I include to make everyone’s days a little bit brighter. As always thank you too all the contributors, and hopefully we will all be underground again in the near future.

Obituary of Dr Paul Driver

In September, my uncle, Dr Paul Driver, died aged 70.

In recent years, Paul took part in occasional caving trips, some with other ULSA members, and helped out at a Give It A Go event. Paul took me on my first caving trip to Dow Cave in 2010, 41 years after his first caving trip (also to Dow Cave) in 1969.

Paul loved caving and walking in the Dales as well as visiting many of the pubs there. He leaves behind his wife Judith, five children and six grandchildren, and is greatly missed.

Paul was a member of ULSA through the 1970s, while working as a researcher at the Department of Animal Physiology and Nutrition at the University of Leeds. He took part in much of the club’s exploration during this time (including in Pippikin Pot and Long Churn Caves), alongside friends such as John Lockwood, Jim Davis, Alan and Dave Brook, and Joe and Alf Latham. He had many entertaining tales, such as Dave Brook ‘lifelining’ him out of The Mohole, and being recruited from a Dales pub to lead a rescue party in Dowbergill Passage.

Move Mountains for Malcolm

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Malcolm Bass was a prominent cave explorer with ULSA, pushing many gnarly water-logged passages in Penyghent Pot, Kirk Bank Cave and elsewhere with contemporaries such as Watty, Andy Tharratt, Paul Monico and many others. He then went on to become a respected mountaineer, putting up new routes in Scotland and heading on numerous expeditions to the greater ranges, all while working as a clinical psychologist for the NHS.

Very suddenly last year, Malcolm suffered a severe stroke and a fundraising campaign, ‘Move Mountains for Malcolm’, was recently initiated to raise the money needed to help Malcolm during this difficult time. It was unanimously decided that a donation of £350 would be made from the Watty Fund towards this cause. Anyone that would like to donate funds towards Malcolm’s recovery can do so here.

Photo: Pete Bolt.

Does Rainfall on The Surface Affect the Water Levels in Caves?

Brendan Hall

On the 17th December 2013 (I think), Rob W, Katie B and Matt D were trapped in King pot after unexpected heavy rainfall. I remember being questioned by cave rescue, who were confused after I asked the question, ‘Does rainfall on the surface affect the water levels in caves?’. At which point they sent me to sit in the police car instead. Unfortunately, CRO misunderstood the highly academic nature of my query, as I assumed this was something that had been studied previously (or maybe they just weren’t in the mood for discussing cave hydrology with me at that time).

Either way, 8 years later, I have returned to answer the question myself. I could have just gone out and bought a commercial pressure sensor based water level logger from a company like Solinst, these robust devices are about the size of a cigar and can log water levels for several months on a single charge. But after finding out these things cost around £500 each I decided maybe it would be better/cheaper to construct my own instead.

Designing and building a DIY water level logger requires much time and patience which, thanks to a global pandemic, I had no shortage of. The BCRA also agreed to pay £500 towards the cost of parts. The DIY devices are around £75 each, but I spent a few hundred pounds on tools/prototypes and breaking delicate components to get to the final design, which in theory can log water levels with cm resolution up to 100m.

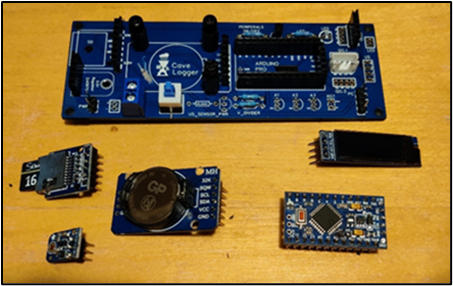

The logger is primarily composed of four modules: an Arduino pro mini microcontroller board, real time clock (RTC), SD card module and a power supply. Various sensors can then be added to suit the needs of a variety of long-term logging projects, monitoring variables such as: temperature, pressure, humidity etc. The modules were mounted on a custom printed circuit board (Fig. 2) to save space and allow the various breakout boards to be added and removed from the PCB with pin header connections. Alongside the core logger modules the PCB can accommodate up to three I2C devices/sensors, three analogue sensors and/or an ultrasonic sensor.

For water level monitoring the logger used a MS5803-14BA piezo-resistive pressure sensor mounted on a sparkfun breakout board with I2C pinouts. The sensor was designed for underwater use up to 14 bars (~140 m). As the pressure sensor was not vented to atmosphere readings could be affected by changes in atmospheric pressure. It should be possible to mitigate the effect of this by normalising the water level data to the point at which the water surrounds the sensor during a flood event using the inbuilt temperature sensor.

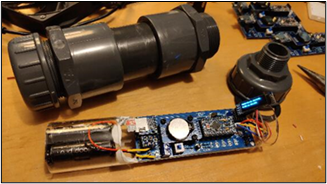

The sensor was potted on the outside of the logger housing in epoxy resin. The logger housing was constructed from a short length of 2-inch U-PVC pipe sealed at both ends with solvent welded end fittings with removable screws caps (Figure 4). The PCB was attached to a slightly smaller pipe which had been cut in half, meaning the circuitry could slide into the main housing with a flush fit.

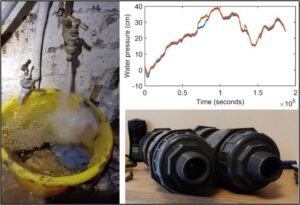

Unfortunately at the time of writing the loggers are deployed in sleets gill cave, and have been tested in my bedroom over the past few weeks. The deviation in pressure reading is caused by fluctuations in atmospheric pressure, which I should be able to compensate for during post-processing of the data.

As well as monitoring fluctuations in underground water I also need to compare this data with rainfall readings. There are numerous tipping bucket gauges owned by the environmental agency around the Dales with rainfall data that can be accessed live via an API. However, rainfall in the dales is highly variable and to obtain a more accurate idea of how much rain has fallen I would be better off using rain radar data instead.

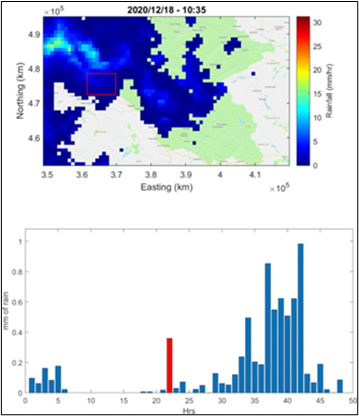

Unfortunately, access to the raw data from the MetOffice’s NIMROD rain radar system is off limits to anyone but the met office themselves and ‘bonafide researchers’. Lucky for me being a PhD student is good enough and my application to access the data was approved. It took me a few days to work out how to interpret the annoying bespoke data format used for the radar data but eventually reduced the data down to a georeferenced 2D array which could be overlaid on a map to show how rainfall changes with time to give mm of rainfall vs time for a given catchment area (see left).

No results yet, but hopefully I should be able to get some interesting results by the end of the year.

Yoga for Cavers

Caroline Nunn

With Lockdown significantly limiting our potential to get outside and stay fit, the BCA provided CHECC with funding to host a Yoga for Cavers series hosted by yours truly. The sessions have been a massive success, getting cavers stronger and more supple (a trait that has never been attributed to a caver since the beginning of time!)

Sessions 1-6 out of 8 are available for all cavers to utilise through the following YouTube links below:

I teach LYT Yoga, the only style of yoga created by a physiotherapist that is anatomically informed and fun. It’s accessible for most bodies and fitness abilities and builds on from one week to another. If you fancy giving it a go, make sure to follow the order of the sequences to get the most out of it! Also, remember that there is no pressure to complete the entire sequence if it feels too much, though I thoroughly recommend The Reset at the start of each sequence if all you can spare is 20 minutes!

Mossdale Great Aven

Mike Butcher

It had been about 8 years since my first and only foray into Mossdale. On that occasion I’d been convinced by Kristian Brook that a wetsuit wasn’t required. That was probably the last time I heeded Kristian’s advice, although fond masochistic memories endure of going across the swims to a rendition of: “my b*llocks fell into the ocean, my b*llocks fell into the sea, my b*llocks shank up to my tonsils, or bring back my b*llocks to me, to me.” With restrictions easing in the Summer I took Adele Ward up on the offer of a second trip around Mossdale on the 6th August. In the intervening years since my last visit she has had spent a lot of time in Mossdale and now knows it very well.

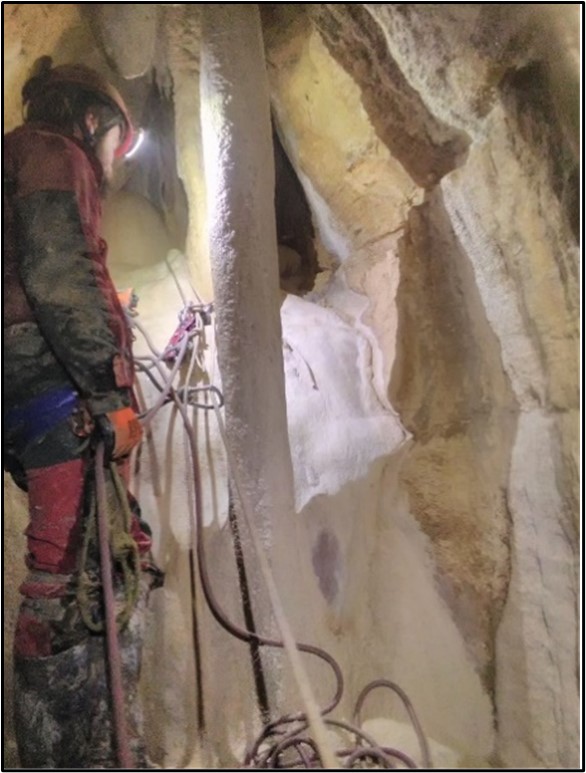

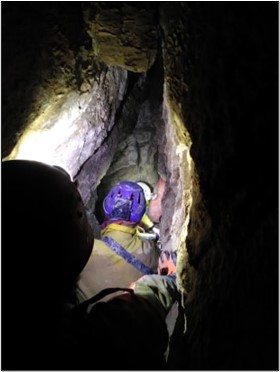

Unfortunately, the first swim was found to be sumped but a pleasant trip was had around the entrance passages and down Far Western Passage. The next trip wasn’t until the 17th September with perfect settled weather we got as far as the Rough Chamber, with my interest being peaked by the supposedly unclimbed Great Aven. A return trip with gear was arranged for the 21st September. However, my enthusiasm to bring all the aven climbing gear I could find was thwarted by my oversight of a lack of a wetsuit. So, a surface reccy of Grassington Moor was had instead. Walking past the impressing shakehole of Howgill Nick Hole, up to the Mossdale memorial cairn, down to Gill House Pot where I explored as a plain clothes caver, then back to the cars via Fossil Pot.

The next attempt was planned for the 28th September. In the interlude I checked with Beardy about the last known attempt to climb Great Aven: “My attempt was a long time ago and was unsuccessful due to the quality of the rock – I remember mud oozing out of the edges of brick sized bits of limestone that I had bolted into…. I retreated to continue living…..” With a slight sense of foreboding, I attempted the climb assisted by Adele. Rob Watson was due to join but had a covid scare so had to isolate. Taking a line a few metres left of Beardy’s, I stayed in a bit of an alcove. At about 10m a poor band of rock was encountered, and with time getting on it seemed a good point to leave it for another day.

Back there on the 3rd of October, this time supported by David Newcombe. This was David first trip into Mossdale, with most of his caving to date being student trips with freshers. I hadn’t caved with David before, so was pleased to see his reserved persona was soon washed away by the Mossdale Beck, to be replaced by enthusiasm and appreciation for what really is a fun and enjoyable cave. The climbing went well, I was finally getting my head round the Rameur Stickup device I had borrowed from Rob, and after some tentative placements I was passed the area of bad rock, and into clear. Having traversed out to the right to avoid an overhanging fluted tube, I was now directly above the bolts left by Beardy. Approximately 16m off the floor. Up above the roof seemed to closed down, but an archway up to the right alluded to an ongoing aven upwards. Time was getting on so we left it for another day. On the way down I attempted to remove the rigging left by the previous party. The mallions were corroded shut so I tried unscrewing the nuts from the bolts, but as I turned the entire bolt swivelled around. Lubricated by mud. I can seen now what Beardy meant. A hacksaw or molegrips might be helpful for next time, failing that a knife to cut out the rope.

Alas, following the trip my work commitments took me up to Scotland, and my attention was absorbed by training for my CDG practical test, which I fortunately passed just before lockdown 2 hit. In my absence Rob, Nathan Walker and Adele had a crack but it was found to be too wet. With the various restrictions and poor weather, no one to my knowledge has been back since. It is ongoing, seemingly towards the surface. There is a slim chance a higher level of development could be encountered. Failing that the potential for a second entrance will be well worth it.

Adventures in France

Alice Smith

Caving for the French seems to use a different timing system to that of student caving in the UK. This meant being picked up at 08:00 on a Thursday to drive along mud tracks through a forest to encounter a tractor waiting near the cave entrance at 08:20. The previous day for those underground had involved blasting a new entrance to Grotte de Preoux and widening a loose “fondou” pitch head 30m from the surface.

The previous time I had been caving had been to the same spot, but had involved ascending this pitch on 30yr old dynamic rope, and helping belay an impromptu bolt climb. “I remember there being roots up here last time – oh that’s because I free-climbed the top section” – Bruno. The aim of that trip had been to use an avalanche detector to locate the top of the aven from the surface. Due to the bolt climb taking place, the surface team had prepared for rescue, making a fire on the surface in -10C and another trip was organised for the surface location.

Back to this trip, Guy, Bruno, Jacob and I all got kitted up before I realised my descender was still sitting in the cupboard back at home. This led to creating a relay, with a descender being shuttled at re-belays, to avoid a total of 40m down-prussiking. At the bottom of the first pitch series, a shower of pebbles came down, leading to me trying to escape around the corner whilst not tripping over the discarded bang wire. Just around the corner was the location of the fondou rock. As well as being crumbly, it was described as the “bassiest thing I’ve ever heard underground” by Jacob. An attempt to find solid spots for the new bolts was followed by the demolition of the flakey wall. This was mostly Guy using a lump hammer while I belayed Bruno adding in an additional two bolts for the pitch head.

Bolts in, a large thwack with the hammer released a large block of fondou, which was disposed of down the pitch along with the rest of the rubble and, resulted in the severing of a spare rope resting at the bottom.

With the newest entrance accessible and “safe”, it was time for Jacob to embarrass himself while de-rigging. Thankfully, his hand jammer only dropped 5m down the 30m pitch after it had been de-rigged. A nice trip, and back in time for lunch.

Trip Log: Simpson’s 17/09/2020

Adam Aldridge

All set to go, the team was heading Dales ward for a run of Simpson’s pull through followed by Herron Pot. Driving full speed ahead, Mike Butcher was at the helm, Adam Aldridge riding shotgun; with Beth Jones and Ben Chaddock in the back, it felt like are union of sorts. Semester one was just about to start, and it was that time of sunny interlude between waves of covid turmoil. The day was bright, optimism in the air – even the encounter of a charged event at the beginning of the drive didn’t skew the mood: Just leaving Leeds, we ran into the scene of a recent crash, a hit and run situation. And it looked like the assailants had taken something from the target’s boot. Pulling over, Mike Butcher got out to assess the scene. People were calling the police and gathering, talking about what might have happened. Soon things were under control, and after a short period of suspicion directed at the somewhat battered caver-car, we were back in hot pursuit of the mission.

On arrival, Simpson’s first, we walked up the hill, and after only a little while being lost, found the entrance. Ben started rigging upfront with Mike; Beth and Adam followed derigging. All went smoothly, and at the last pitch up towards Valley Entrance, we fancied a challenge. Mike, bold as usual, proceeded it as a free climb, utilising a couple of bolts with his cow’s tails for protection. Adam, inspired by Mike’s effort repeated the climb somewhat more smoothly after seeing the beta. Ben, after patiently waiting in the streamway for all three of us to make the ascent, confidently began to follow in our footsteps. He quickly climbed to a point where both Mike and Adam had traversed to the right, clipping the p-bolts. Then, unwaveringly, he proceeded to follow a harder line to the left, completely unprotected. It was a continuation that Mike had previously edged up but didn’t feel keen on.

After completing Simpson’s, a brief conversation with a man who had just been paragliding was followed by our swift and efficient transit to, and completion of Herron Pot. I was personally impressed with the sheer determination, grit, and all-round will power that we executed in conquering Herron with such competency, and not instead falling into the temptation of spending a lovely few hours in the sun at the Marton Arms’ beer garden with a couple of pints and a bowl of chips. Because we most certainly didn’t do anything like that – perish the thought!